Little Adventures

*

Forefathers

Johann Hufnagel stood by his forge in 1835 and stared angrily out into the summer

afternoon. His business was in trouble. In trouble, not because he was a poor blacksmith,

but because of the Zollverein, which had abolished the tariffs that had formerly

protected his trade from competition. Now, the neighborhood farmers no longer came

to him to make their nails, hinges, or hay forks, but, instead, bought these things

ready made from peddlers. Johann's business was slowly dying. And then, just the

previous night, he had been at the village reading club, and had heard the stories

of a man newly returned from America. Stories of a plentiful wilderness being peopled

by German immigrants. John had been at the meeting, too, and, as they walked home

in the darkness, his son had spoken of emigrating to this wonderful sounding land

called America. Now, Johann stood in his quiet, familiar blacksmith shop and thought

what it would be like to move to America at his age, leaving a lifetime of friends

and work behind. No, he could never ask Katherina to leave Schneppenbach. Still,

he knew in his heart, and in his head, that John's future was in America, and not

here working as a laborer in overcrowded Bavaria. Johann didn't know which fact,

his having to stay or John's having to go, made him angrier.

Johann Hufnagel stood by his forge in 1835 and stared angrily out into the summer

afternoon. His business was in trouble. In trouble, not because he was a poor blacksmith,

but because of the Zollverein, which had abolished the tariffs that had formerly

protected his trade from competition. Now, the neighborhood farmers no longer came

to him to make their nails, hinges, or hay forks, but, instead, bought these things

ready made from peddlers. Johann's business was slowly dying. And then, just the

previous night, he had been at the village reading club, and had heard the stories

of a man newly returned from America. Stories of a plentiful wilderness being peopled

by German immigrants. John had been at the meeting, too, and, as they walked home

in the darkness, his son had spoken of emigrating to this wonderful sounding land

called America. Now, Johann stood in his quiet, familiar blacksmith shop and thought

what it would be like to move to America at his age, leaving a lifetime of friends

and work behind. No, he could never ask Katherina to leave Schneppenbach. Still,

he knew in his heart, and in his head, that John's future was in America, and not

here working as a laborer in overcrowded Bavaria. Johann didn't know which fact,

his having to stay or John's having to go, made him angrier.

* * * * *

On a shining autumn afternoon in 1853, John Hufnagel paused for a moment as he was harvesting his wheat. Looking down the hill towards his farmhouse, he listened for the squall of his newborn son, Andrew. Then John leaned on his scythe and fell to wondering what Andrew's life would be like. John well remembered his own youth and his boarding a ship in Rotterdam and getting off again in Baltimore. He remembered the years he had spent at Lucinda Furnace making pig iron for shipment down river to Pittsburgh. Most of all he remembered how he and his wife Catherine, with much help from other German families, had carved this productive and pleasantly situated farm out of the howling wilderness of Clarion County, Pennsylvania. Then, John turned back to his work and began humming. Andrew would be just fine. Anything was possible here in America.

* * * * *

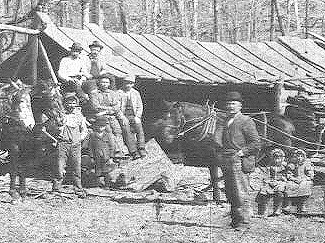

Early one morning in the year 1900, Andrew Hufnagel took down his gun and walked to the Ginkle Farm. There he sat on a stump and awaited the dawn. At first light he saw an antler buck in the distance. As the buck ran across the field, he fired once, twice and a third time; and the deer fell dead on the ground. Later, as Andrew used a rope to drag his deer home over the snow, he stopped midway to catch his breath. Leaning against an old oak tree, he was taken with the beauty of the morning and fell to remembering other winter mornings. He remembered churning butter in the spring house as a boy and how he had so hated the cold. He remembered the welcome wintertime warmth of his blacksmith shop in Marble. And then he smiled, recalling snowy mornings in lumber camps where he had done the iron work, his wife, Lena, had done the cooking, and their youngest son Henry had ran half wild through the camp getting into all sorts of mischief. Andrew gave himself a shake, picked up the rope, and again began dragging his deer homeward. He had already decided to get its head mounted, and now he began inventing the tall tale that he would tell of this morning, the morning he had shot his hat rack.

* * * * *

In June of 1945, Henry Hufnagel got a telephone call from Jeanne and Lee in Buffalo announcing the birth of a son. Later on that day, up to the attic looking for baby things that might be of use to the new parents, Henry noticed a framed advertisement from 1915 for the Citizens Trust Company, A Progressive Conservative Bank Whose Directors Direct Its Affairs. He smiled at the old slogan and at his own name listed there as Assistant Treasurer. That had been back when many believed him to be a roughneck from the woods of Fryburg who would never make much of a banker. Now at the age of 65, he was president of the bank in Clarion and had long ago lived down his early reputation as a rowdy and a ladies man. Reminiscing, Henry walked back downstairs to talk with Lizzy about those early days, back when they were courting.

* * * * *

As Leon Hufnagel began removing the original windows from his house in the Spring of 1994, he couldn't help but remember the day in 1948 when they had first been installed. This was the first large house that he had designed as an independent architect. When he built it, there had been only two other houses on the street. Now the neighborhood was full up, but still his home looked modern enough, with its greenhouse poking out of the south side. Lee well remembered moving back to Clarion after the war and the first night that he and Jeanne and the kids slept here in the unpaved wilderness of Third Avenue. Now as Lee began working the first window loose from its frame, he remembered other projects and how he had used these to teach his sons to wield a hammer, cut straight with a saw, and stick to a job until it was finished. As the window came loose into Lee's hands, there was his son, Hank, on the other side, joking about how the windows were falling out of the old place, ready to help his father with the current project, just as in the old days.