Little Adventures

*

Making Kaleidoscopes

By 1988 I had my own small software business in Clarion, Pennsylvania, a small town

in the northwestern woods of the state and home to Clarion University of Pennsylvania,

where I ran the computer center in the early 1980s. Pam and I had married and our

son Pete was just 5 years old. One evening I showed him two treasures left over from

my boyhood — The Boy Mechanic and The American Boy's Handy Book.

By 1988 I had my own small software business in Clarion, Pennsylvania, a small town

in the northwestern woods of the state and home to Clarion University of Pennsylvania,

where I ran the computer center in the early 1980s. Pam and I had married and our

son Pete was just 5 years old. One evening I showed him two treasures left over from

my boyhood — The Boy Mechanic and The American Boy's Handy Book.

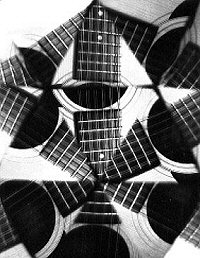

We leafed through these ancient, broken volumes learning how to do things the way they were done 50 and 100 years ago. In our imaginations we built snowshoes to help us wade through the deep snow to our muskrat traps, mechanical tanks that fired wooden bullets as they trundled across the floor, and fire balloons to send skyward at sunset. Horrible things to some, but interesting to think about nonetheless. In the Handy Book we came across a piece explaining how to construct a kaleidoscope and decided to go further than just imagining. The next day we bought a mirror and had it sliced into three long skinny strips. Back home, we used duct tape to construct a long triangular tube from the three pieces. That was all there was to it. Now we had a big kaleidoscope and we proceeded to examine everything in sight through it.

A kaleidoscope uses mirrors to create a symmetric six sided image. I dug around in my junk drawers and found two other symmetric image makers for Pete to look at. One distorts the image with a strong lens, and the other uses a faceted lens to give a dragon's eye view of the world. Pete loved all three toys for twenty minutes and then lost interest. I can't blame him, I did myself. How much standing around looking through a tube can anyone take ("Lots!" would say Tycho Brahe). Pete had to take a shower about then and so I was left alone to think about making a better kaleidoscope. What I really needed was a computer program which would allow me to draw an image just like a kaleidoscope. Then Pete could make kaleidoscopic art, which might better hold his interest because he could experiment endlessly and print out his best results to show to others. At that time I had the hottest micro computer on the market, and I knew I could write a decent version of the program. The only problem was, I needed to make a living. I had my plate full with writing a commercial 3D CAD program. The kaleidoscope program would just have to wait, but only until my work program was complete and a success.

* * * * *

So the years passed again, and each year computers evolved and PartyCAD demanded improvement. But each year at Christmas, I thought about all the small programs I wanted to write someday. A pattern painting program, a polyhedron pattern drawer, my version of ESCHER and a kaleidoscope program. In 1993 the waiting ended, and I spent a wonderful year combining the four ideas into a single program called SymmeToy.